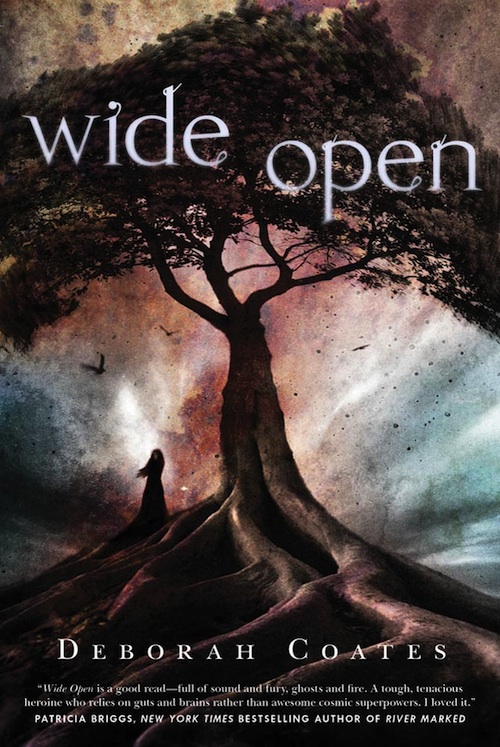

Here is an excerpt from Wide Open by Deborah Coates, one more ghostly tale to usher in Halloween and bring Ghost Week to a close…

When Sergeant Hallie Michaels comes back to South Dakota from Afghanistan on ten days’ compassionate leave, her sister Dell’s ghost is waiting at the airport to greet her.

The sheriff says that Dell’s death was suicide, but Hallie doesn’t believe it. Something happened or Dell’s ghost wouldn’t still be hanging around. Friends and family, mourning Dell’s loss, think Hallie’s letting her grief interfere with her judgment. The one person who seems willing to listen is the deputy sheriff, Boyd Davies, who shows up everywhere and helps when he doesn’t have to.

As Hallie asks more questions, she attracts new ghosts, women who disappeared without a trace. Soon, someone’s trying to beat her up, burn down her father’s ranch, and stop her investigation. Hallie’s going to need Boyd, her friends, and all the ghosts she can find to defeat an enemy who has an unimaginable ancient power at his command.

1

When Sergeant Hallie Michaels arrived in Rapid City, South Dakota, she’d been traveling for twenty-four hours straight. She sat on the plane as it taxied to the gate and tried not to jump out of her skin, so ready to be up, to be moving, to put her head down and go. And Lord help anyone who got in her way.

She hadn’t been able to reach her father or anyone else by phone since she’d gotten the news, just contact with her commanding officer—We’re sorry, your sister’s dead. Here’s ten days’ compassionate leave. Go home.

Three sharp bongs, and the seat belt light went out. The plane filled with the sound of seat belts snapping, people moving, overhead doors opening up. The woman in the seat next to Hallie’s was still fumbling with her buckle when Hallie stepped past her into the aisle. She felt raw and sharp edged as she walked off the plane and up the Jetway, like rusty barbed wire, like she would snap if someone twisted too hard.

Halfway down the long wide concourse, ready—she was—for South Dakota, for her sister’s funeral for—

Goddamnit. Eddie Serrano’s ghost floated directly in front of her, right in the middle of the concourse. She swiped a hand across her eyes, hoped it was an artifact of no sleep and too much coffee, though she knew that it wasn’t.

He looked like he’d just stepped out of parade formation—crisp fatigues, pants neatly tucked into his boots, cap stiff and creased and set on his head just exactly perfect. Better than he’d ever looked when he was alive—except for being gray and misty and invisible to everyone but her.

She thought she’d left him in Afghanistan.

She drew a deep breath. This was not happening. She was not seeing a dead soldier in the middle of the Rapid City airport. She wasn’t. She squared her shoulders and walked past him like he wasn’t there.

Approaching the end of the concourse, she paused and scanned the half-dozen people waiting just past security. She didn’t see her father, had almost not expected to see him because—oh for so many reasons—because he wouldn’t want to see her for the first time in a public place, because he had the ranch and funeral arrangements to take care of, because he hated the City, as he always referred to Rapid City, and airports, and people in the collective and, less often though sometimes more spectacularly, individually.

She spotted a woman with straight blond hair underneath a cowboy hat standing by the windows. Brett Fowker. Hallie’d known Brett since before kindergarten, since a community barbecue when they were five, where Brett had told Hallie how trucks worked and Hallie had taken them both for what turned out to be a very short ride. Brett was all right. Hallie could deal with that.

She started forward again and walked into a cold so intense, she thought it would stop her heart. It felt like dying all over again, like breath froze in her lungs. She slapped her hand against the nearest wall and concentrated on breathing, on catching her breath, on taking a breath.

She looked up, expecting Eddie.

But it was her sister. Dell.

Shit.

Suddenly, Brett was there, a hand on her arm. “Are you all right?” she asked.

Hallie batted her hand away and leaned heavily against the wall, her breath sharp and quick. “I’m fine!” Her voice sounded rough, even in her own ears.

Dell looked exactly as she had the last time Hallie’d seen her, wearing a dark tailored shirt, jeans with a hole in one knee, and cowboy boots. She was a ghost now and pretty much transparent, but Hallie figured the boots were battered and scuffed because she’d always had a favorite pair that she wore everywhere. Even when she’d dressed up sometimes, like no one would notice the boots if she wore a short black dress and dangly silver earrings. And no one did—because it was Dell and she could carry something like that off, like it was the most natural thing in the world.

Hallie scrubbed a hand across her face. Goddamnit, Dell. She wasn’t going to cry. She wasn’t.

“I’m sorry, Hallie. I’m sorry.”

Brett said it over and over, like a mantra, her right hand a tight fist in Hallie’s sleeve. In sixth grade after Hallie’s mother died, she and Brett had made a no-hugging-ever pledge. Because no one had talked to Hallie that whole week, or looked her in the eye—just hugged her and handed her casserole dishes wrapped in aluminum foil.

Trust Brett to honor a pact made twelve years ago by eleven-year-olds.

“Brett,” Hallie said, “I—”

“Hallie!” Suddenly someone was hugging her. “Oh god, Hallie! Isn’t it awful?”

Lorie Bixby grabbed her around the neck, hugged her so tight, Hallie thought she might choke. “It can’t be right. I know it’s not right. Oh, Hallie . . .”

Hallie unwound Lorie’s hands from her neck and raised an eyebrow at Brett, because Lorie hadn’t been particular friends with Brett or Hallie back in school, though they’d done things together, because they lived close—for certain definitions of close—and were the same age. Hallie hadn’t seen her since she’d enlisted.

Brett raised her left shoulder in a half shrug, like she didn’t know why Lorie was there either, though Hallie suspected it was because Brett hadn’t wanted to come alone.

They were at the top of the stairs leading down to the luggage area and the parking lot. To Hallie’s left was a gift shop full of Mount Rushmore mugs and treasure maps to gold in the Black Hills. To her right was a café. It beckoned like a haven, like a brief respite from Afghanistan, from twenty-four hours with no sleep, from home.

But really, there was no respite. This was the new reality.

“Tell me,” Hallie said to Brett.

Brett hadn’t changed one bit since Hallie’d last seen her, hadn’t changed since she’d graduated from high school, except for the look on her face, which was grim and dark. She had perfect straight blond hair—cowgirl hair, Hallie and Dell had called it because all the perfect cowgirls in perfect cowgirl calendars had hair like Brett’s. She was wearing a bone-colored felt cowboy hat, a pearl-snap Western shirt, and Wranglers. “Tell you?” she said, like she had no idea what Hallie was talking about.

“What happened,” Hallie said, the words even and measured, because there were ghosts—Dell’s ghost, specifically—in the middle of the airport, and if she didn’t hold on tight, she was going to explode.

Brett drew a breath, like a sigh. “You should talk to your daddy about it.”

“Look, no one believes it was really suicide.” Lorie leaned toward them like this was why she’d come, to be with people, to talk about what had happened.

“What?” No one had mentioned suicide to her—accident, they’d said. There’s been a terrible accident.

“No one knows what happened yet,” Brett said cautiously, giving Lorie a long look.

“Tell me,” Hallie said, the words like forged nails, iron hard and sharp enough to draw blood.

Brett didn’t look at Hallie, her face obscured by the shadow of her hat. “They say,” she began, like it had all happened somewhere far away to people who weren’t them. “She was out driving over near Seven Mile Creek that night. Or the morning. I don’t know.” Like that was the worst thing—and for Brett, maybe it was—that she didn’t have all the particulars, the whys and wherefores. “She wracked her car up on a tree. There was no one else around. They’re saying suicide. But I don’t— No one believes that,” she added quickly. “They don’t.” As if to convince herself.

“Dell did not commit suicide,” Hallie said.

“Hallie—”

She walked away. This was not a discussion.

She didn’t look to see if Brett and Lorie were behind her until she was halfway to the luggage carousel.

Five minutes later, they were crammed into Brett’s gray Honda sedan. Hallie felt cramped and small sitting in the passenger seat, crushed under the low roof. Lorie sat in the back, an occasional sniff the only mark of her presence.

Brett turned the key in the ignition, the starter grinding before it caught. Hallie felt cold emanating from Eddie’s and Dell’s ghosts drifting behind her in the backseat. Though Lorie didn’t act as if she could feel them at all.

“She called me,” Brett said as she pulled out of the parking lot.

“What?” Because Dell and Brett hadn’t been friends.

“Yeah, right out of the blue,” Brett said.

“When?”

“Monday morning. That morning.” Brett swallowed, then continued. “She wanted me to skip classes—I’m working on a master’s in psychology, you know—well, you don’t know, I guess.” It didn’t surprise Hallie. Brett had always wanted to know how things worked, even people. She’d been a steady B student in high school, but she worked until she knew what she wanted to know or got where she wanted to get.

“I’m thinking about University of Chicago for—” Brett stopped, cleared her throat, and continued. “She said she wanted to celebrate.”

“And she called you?”

“Shit, I don’t know, Hallie,” Brett said. “She called, said she wanted to celebrate. Suggested horseback riding up along, well, up along Seven Mile Creek. It was weird.”

“Maybe she didn’t have anyone to ride with anymore.”

“She didn’t have a horse.”

“What?” Because Dell had always been about horses.

“She’d been gone,” Brett said, like they didn’t have horses outside western South Dakota.

“Did you go?”

Brett was silent while she maneuvered through the sparse late-morning traffic and onto the interstate, headed east. They had an hour, hour and a half depending, to get to Taylor County and the ranch. Or to the funeral home in town. Hallie wasn’t looking forward to either one.

“She canceled at the last minute,” Brett finally said. “I’d already brought the horses up, was getting ready to load them in the trailer when she called. She said she’d been mistaken.”

“Mistaken?”

“Yeah . . . I hadn’t seen her but one night at the Bob since she’d been home. She said she wanted to celebrate, I don’t know, something. And then she canceled.”

Hallie’s hand rapped against the underside of her knee until she realized she was doing it and made herself stop. “Did she say anything?”

“When she canceled?” Brett shook her head. “She just said something came up. But that’s where they found her, Hallie. Up on the Seven Mile.”

Jesus.

Hallie didn’t want to be riding in this car, didn’t want to be listening to any of this. She wanted to move, to . . . shoot something. Because Dell hadn’t killed herself. She hadn’t. If no one else would say it, Hallie would.

2

They rode in silence for the next half hour. Hallie’d thought knowing more about how Dell had died would help, would make coming home easier to handle. She hadn’t counted on seeing Dell’s ghost, on discovering that the fact of how she died— Dell drove her car into a tree—told her pretty much nothing at all.

Lorie put her hand over the back of the seat and let it rest on Hallie’s shoulder, like Hallie could make things right. Find out what happened. Beat someone up. Do something.

Dell’s right here, Hallie wanted to say. Can’t you see her?

Lorie began to talk, to tell Hallie about working at some new company in West Prairie City with Dell, about how that was the reason Dell had come back, about how Hallie should have seen her because she had been . . . well, she’d been . . . well . . . yeah.

More silence.

Brett dropped off the interstate onto old State Highway 4, back in Taylor County, finally. Things began to look familiar.

Familiar and different because she had changed and the county had changed. The track up to the Packer ranch, which they’d just passed, had gone to prairie. The Packers had tried to sell up two years before Hallie left, and then they’d just disappeared, left the ranch to the bank, let it all go. Hallie wondered what the buildings were like up there, because things didn’t last on the prairie; even things you thought were permanent could disappear in the dry and the cold and the endless wind.

Brett turned off the state highway onto an uneven county road. Hallie looked at her. “Aren’t we—?” She stopped. “We’re going to the ranch, right?”

Brett bit her bottom lip. “Your daddy says you’re going to pick the casket. And . . . the rest of it.”

Hallie gave a sharp half laugh and pinched the bridge of her nose. Of course he did. When their mother died, she and Dell had picked out the casket with help from Cass Andersen and, if she remembered right, Lorie’s mother. Because her father could wrestle an angry steer and rebuild an old tractor engine and even mend a pair of ripped jeans, but he couldn’t face the civilized part of death, when the bodies were cleaned up and laid out and someone had to decide how to dress them and fix their hair and what was going to happen for the rest of eternity.

Brett looked straight ahead. “Yeah,” she said. “I hope—”

There was a loud thump from underneath the car. The steering wheel jumped in Brett’s hands, and the car veered sharply to the right. Brett had been doing seventy on the flat straight road, and it took long adrenaline-fueled seconds of frantic driving—punctuated by “My god, what’s happening!” from Lorie in the backseat—to avoid both ditches and bring the car to a shuddering stop on the graveled shoulder.

Hallie was up and out of the car while the dust was still settling. “Flat tire,” she said unnecessarily. No one answered her or got out of the car to join her, either, and after a minute, she stuck her head back in. Brett looked at her, face gone white, then sniffed and poked ineffectually at her seat belt. Lorie was silent in the backseat, her knees pulled up to her chest as if this were the one last thing she’d both been waiting for and dreading. Hallie reached a hand back through the open window, then withdrew.

Jesus!

Brett finally got out of the car, though so slowly, it set Hallie’s teeth on edge. Brett had always been the calm one, the one who maintained an even keel, no matter what. She’d had this way of standing, back in high school, with a thumb tucked in her belt and one hip cocked that used to drive the boys wild. Brett hadn’t even paid attention to those boys, more interested in barrel racing and the cutting horses her daddy trained and sold to celebrity ranchers for twenty-five thousand dollars apiece.

But now, she was slow, like she’d aged five hundred years, standing by her door for what felt to Hallie like an eternity—get you shot in Afghanistan, standing around like that, get your head blown right completely off. Brett reached back into the car for the keys, knocking her hat against the door frame; her hand shook as she set it straight. She stood for a minute with the keys in her hand, like she couldn’t remember what to do with them.

Finally—finally!—she walked to the trunk. Hallie’d already paced around the car and back again. Brett’s hand was still shaking as she tried once, twice, three times to slide the key into the keyhole. Hallie couldn’t stand it, grabbed the keys, opened the trunk, and flung the lid up so hard, it bounced back and would have shut again if Hallie hadn’t caught it with her hand. It wasn’t Brett or Lorie sniffling in the backseat or the flat tire or Dell’s death or even Dell the ghost hovering off her left shoulder she was pissed at. It was all of that and not enough sleep and twenty-four hours out of Afghanistan and the sun overhead and the way the wind was blowing and the gravel on the shoulder of the road and the feel of her shirt against her skin.

“Hallie—,” Brett began.

“I got it,” Hallie said. She shifted her duffel to one side and pulled out the spare tire, bounced it on the ground—at least it wasn’t flat. Lucky it wasn’t flat, because in her present state of mind, she could have tossed it into orbit.

Brett didn’t say anything, and Hallie didn’t know if she was relieved to have one thing she didn’t have to take care of or smart enough to know that Hallie just needed one more thing before she lost her shit completely. The sun had dropped behind a band of clouds, and the breeze had shifted around to the northwest. The temperature had dropped maybe seven degrees since they’d left the airport. Hallie had a jacket in her duffel bag, but she was damned if she was going to waste time getting it out. She fitted the jack against the frame and cranked it up until the wheel was six inches or so off the ground.

She realized she didn’t have a lug wrench, went back to the trunk to look, tossed out her duffel, an old horse blanket, two pair of boots, and a brand-new hacksaw. She found a crowbar and a socket wrench, but no lug wrench. She could hear the distant sound of a car, though in the big open, the way sound carried, it could have been a mile or five miles away.

She stopped with the crowbar in her hand because she wanted to smash something. She hadn’t slept, she hadn’t eaten, her sister was dead, and when this was done, she’d still have to go to the funeral parlor and pick out a casket. She was cold and she was hungry. She had a goddamned flat tire in the middle of nowhere, and she couldn’t fix it, because there was no. Fucking. Lug wrench.

“Brett!”

“Yeah?” Brett reappeared from wherever she’d been, probably just the other side of the car.

“Where’s the lug wrench?”

Brett bit her lip, looked into the trunk, like maybe Hallie had just missed it. She frowned. “Daddy might have taken it last week for his truck.”

“Might have? Might have?” Hallie’s voice was low and very, very quiet. “Jesus fucking Christ on a stick!” By the time she got to stick, she was yelling. Loudly. The useless crowbar gripped so tight in her hand, she’d lost the feeling in the tips of her fingers.

“You live on the god. Damned. Prairie. We haven’t seen another car for the last twenty minutes. You’re driving through the deadest cell phone dead zone in America. Did it not fucking occur to you that you might need a lug wrench?”

“Need a hand?”

Hallie turned, crowbar raised, pulling it up sharp when she found herself facing a cop—sheriff ’s deputy to be precise—dressed in khaki and white and so goddamned young looking.

Shit.

He held up a hand. “Whoa.” A smile, like quicksilver, crossed his face. He said, “I didn’t mean to startle you. I thought maybe you could use some help.”

He had dark gray eyes, short dark blond hair cut with painful precision, and was thin, more bone than flesh. His black sports watch rested uncomfortably against his wrist bone. He had an angular face that wasn’t, quite, still blurred by youth. He was not so much handsome as pretty—features barely marred by life. Older than me, Hallie realized, but still looking so, so young.

“We got a flat tire.” Suddenly Lorie was scrambling out of the backseat. “Just—pow!—a blowout, you know. Scary! And Hallie’s just home from—” Hallie’s glare stopped her cold. “—from overseas,” she said lamely, then sucked in a breath and went on, like things— Hallie—could slow her down, but not for long. “It’s been horrible,” she said. “Everything’s been horrible. And this just sucks.” Then she started to cry and actually looked horrified at herself for crying. Hallie figured she’d been shooting for something normal—flirting with the cute deputy sheriff—and been slammed by the fact that they were all here because someone had actually died.

Hallie was horrified, too, because instead of wanting to put an arm around Lorie and tell her it was all right, that they’d get the tire fixed, that things would get better from here, she still wanted to smash something.

It was Brett who took Lorie’s arm and led her away to the front of the car, grabbing a box of tissues from the front seat. The deputy went back to his car and opened the trunk, returning with a lug wrench. He bent down and started loosening the wheel.

“You should really keep a full emergency kit on hand,” he said, loosening the nuts—up, down, over, back. “It gets kind of empty out here.”

“You think?” Hallie’s voice sank back into that dangerous quiet register again. She dumped the crowbar back into the trunk because she really was going to hit something if she didn’t watch it.

Five minutes later, he was finished, wiping his hands on a starched white handkerchief he’d pulled out of what appeared to be thin air. “That should hold until you can get to the garage,” he said. “You’ll want to—”

“It’s not my car,” Hallie said. Who the hell was this guy? He hadn’t been around when she’d left; she was sure of it. She’d have remembered him. He was so, well, beautiful, she couldn’t stop looking at him, though he was not her type—too clean cut. So fucking earnest, too. It pissed her off.

“Oh,” he said. “I’m—”

“Deputy Boyd Davies.” Lorie was back, looking more composed, but with red eyes and a blotchy face. “This is Hallie Michaels. We picked her up at the airport. She’s home because her sister . . . because she—”

“Oh,” the deputy said again. His face thinned down. He looked from Hallie to Lorie to Brett and back to Hallie. “I’m sorry,” he said.

Hallie wanted him gone, wanted the world closed back down. “Thanks,” she said. “Couldn’t have done it without you. But we’ve got to—” She pointed vaguely at Brett and the car and the entire open prairie north of where they were standing. “—go now.”

“I—” The deputy had started talking at the same time she had. He stopped, and when she had finished, he said, “I could follow you to Prairie City. Make sure you get there all right.”

“I don’t—,” Hallie began.

Brett interrupted her. “That’d be good,” she said.

“I can drive,” Hallie said, like that was the problem.

“I bet he has to go that way anyway,” Lorie said.

Though Hallie wanted to argue—wanted an argument—she couldn’t think of an actual reason. “Fine,” she said. “Fine.”

The deputy nodded, and Hallie realized that he’d been going to follow them anyway, no matter what they’d said, which pissed her off again—or, actually, still.

“Who is that guy?” she asked when they were back on the highway.

“He’s new,” Lorie said. “Well, like, a year. Isn’t he cute? I mean, he’s really good looking. Everybody thinks he’s, like, the best-looking thing ever. And he is. But he’s kind of quiet.” And that was familiar— finally—something she remembered about Lorie, that she liked to talk about boys. In detail. For hours.

Though whatever today was, it wasn’t normal, or familiar. Dell’s ghost settled in beside Hallie, drifting cold as winter right up against her shoulder, to remind her.

Deborah Coates © Wide Open 2012